Cemented carbide valve balls, with their extremely high hardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance, are widely used in valves operating under harsh conditions. Their wear failure is usually the result of multiple factors acting together, requiring a systematic investigation.

I. Preliminary Observation of Failure Characterization First, carefully observe the failed cemented carbide valve ball and its mating seat macroscopically and microscopically (preferably using a magnifying glass or stereomicroscope), recording the wear morphology:

1.1 Uniform Wear: The overall size of the ball decreases uniformly, and the surface is smooth. This usually indicates normal abrasive wear, but if the lifespan is too short, the operating conditions need to be reviewed.

1.2 Scratches/Grooves: The surface has unidirectional or network-like deep grooves. This strongly indicates the presence of hard particles (abrasives), possibly originating from the media, pipe rust, or external intrusion.

1.3 Pitting/Pitting: Localized small pieces of material peeling off the surface. Possible causes: cavitation, particle impact, internal material defects (such as porosity, inclusions).

1.4 Surface Material Adhesion: A layer of other material (such as soft material transferred from the valve seat) adheres to the surface of the sphere. This indicates adhesive wear.

1.5 Corrosion Marks: The surface loses its metallic luster, showing rust spots, discoloration, or honeycomb-like pits. This indicates chemical or electrochemical corrosion.

1.6 Cracks or Fractures: Radial or network cracks appear, or even localized chipping. Causes may include overload, impact, thermal stress, or material brittleness.

II. Operating Conditions and Media-Related Causes

2.1 Abrasive Particles in the Media: Check the integrity of the media filtration system and analyze the media composition and solid particle content. Weld slag, sand, rust, catalyst powder, crystals, etc., in the pipeline cause severe three-body abrasive wear, which is the most common cause of rapid failure.

2.2 Cavitation: Check if the valve pressure differential is too large (especially in pressure-reducing applications) and if there are abrupt changes in the flow channel design. When the local pressure is lower than the vaporization pressure of the medium, bubbles are generated. These bubbles collapse in the high-pressure area, and the instantaneous shock wave erodes the material surface. Dense pinhole-like or honeycomb-like pits appear on the surface, often occurring on the downstream side of the cemented carbide valve ball.

2.3 Corrosion: Verify the compatibility of the medium's chemical composition (pH value, Cl- ion concentration, etc.), temperature, and materials. Carbide has good corrosion resistance, but it is not universally effective. Electrochemical corrosion: The cobalt binder phase of carbide may be selectively corroded in some acidic or alkaline media, leading to the shedding of WC particles. Erosion corrosion: Corrosive media accelerate material loss under high-speed erosion.

2.4 Excessive Pressure and Flow Rate: Compare the valve's actual operating pressure/flow rate with the design rating. Excessive pressure and flow rate cause contact stress to exceed the material's tolerance limit, accelerating fatigue wear; high-speed erosion exacerbates wear.

III. Matching and Installation Issues

3.1 Incompatible Valve Seat Material: Confirm that the hardness and type of the valve seat material are properly matched with the cemented carbide valve ball. If the valve seat material is too hard (e.g., both are cemented carbide), it may cause a hard-on-hard contact, making it highly sensitive to minor alignment errors or impurities, easily leading to brittle fracture. If the valve seat is too soft (e.g., PTFE, copper alloy), although the seal is good, abrasive particles can easily embed in the soft material, continuously scratching the hard ball.

3.2 Poor Installation and Alignment: Check the installation accuracy and wear condition of the valve cavity and drive rod. Misalignment between the valve ball and seat leads to uneven wear (severe wear on one side). Uneven preload spring force can also cause similar problems.

3.3 Improper Preload: Adjust the preload according to the valve manufacturer's requirements. Excessive preload increases the opening and closing torque, accelerates wear, and may even crack the valve seat or valve ball. Insufficient preload results in incomplete closure, causing micro-leakage and erosion wear between the sealing surfaces.

IV. Quality Issues of Cemented Carbide Valve Balls

4.1 Material Composition and Microstructure Defects: Metallographic analysis and density determination are required, necessitating a specialized laboratory. Low or uneven cobalt content leads to insufficient toughness and brittleness. Coarse or uneven WC grains reduce wear resistance. Pores, inclusions, and microcracks become fatigue sources, propagating under cyclic stress and causing material spalling.

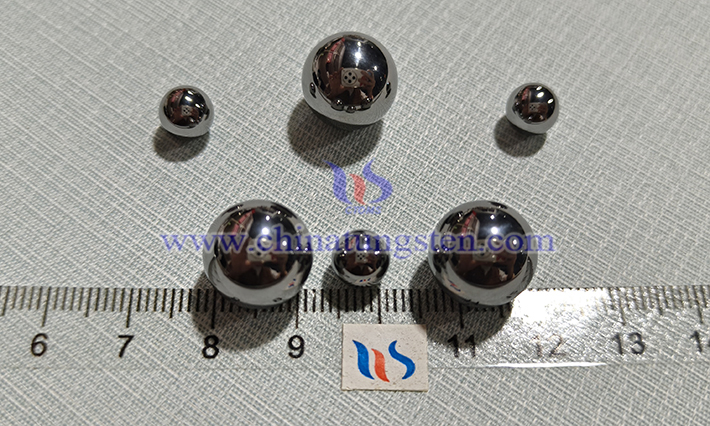

4.2 Manufacturing Process Issues: Hardness (HRA) and surface roughness (Ra) must be tested. Cemented carbide valve balls typically require mirror polishing. Insufficient sintering results in low density, and substandard hardness and strength. Poor surface treatment leaves residual surface stress or microcracks after grinding and polishing.

4.3 Insufficient Geometric Accuracy: Measured using a micrometer and roundness meter. Out-of-tolerance roundness and sphericity affect sealing line contact, causing localized high pressure and leakage wear.

V. Operation and Maintenance Issues

5.1 Opening and Closing Frequency and Method: Inspect whether the valve is being used in inappropriate regulating applications (ball valves are generally recommended to be fully open or fully closed). High-frequency opening and closing accelerates fatigue wear cycles. When partially open, high-speed fluid causes severe erosion of the local sealing surface.

5.2 Lack of Lubrication: For some designs, it is necessary to periodically inject grease to lubricate the sealing surface and remove impurities.